Reverse engineering the MacBook clamshell mode

Closing the MacBook lid with an external monitor connected can turn off and disable the internal display. Let's figure out how macOS does that and bypass the lid sensors.

January 17, 2023

You just got a large, Ultrawide monitor for your MacBook. You hook it up and marvel at the amount of pixels.

You notice you never use the MacBook built-in display anymore, and it nags you to have it in your lower peripheral vision.

Closing the lid is not an option because you still use the keyboard and trackpad, maybe even the webcam and TouchID from time to time. So you try things:

- you try turning off the display by lowering the brightness completely. 🤔 hmm ok but now:

- your mouse wanders to that screen sometimes

- some windows get lost in there

- ..and you still waste GPU cycles for rendering 6 million unused pixels

- you mirror the monitor to the built-in screen. nice, this solves the first two issues!

- ok but why did the resolution change? do I have to change it back every time I do this??

- wait, why don’t I get notifications anymore?! oh. there’s a setting for that

- you walk away from the desk, the screen goes to sleep

- you come back, the screen is now on something like 6% brightness, not completely off anymore

- ok, press

Brightness Downagain, I can live with that - oh, mirroring got disabled as well.. at least there’s

Cmd+Brightness Down

- ok, press

Why isn’t there a way to actually disable this screen?

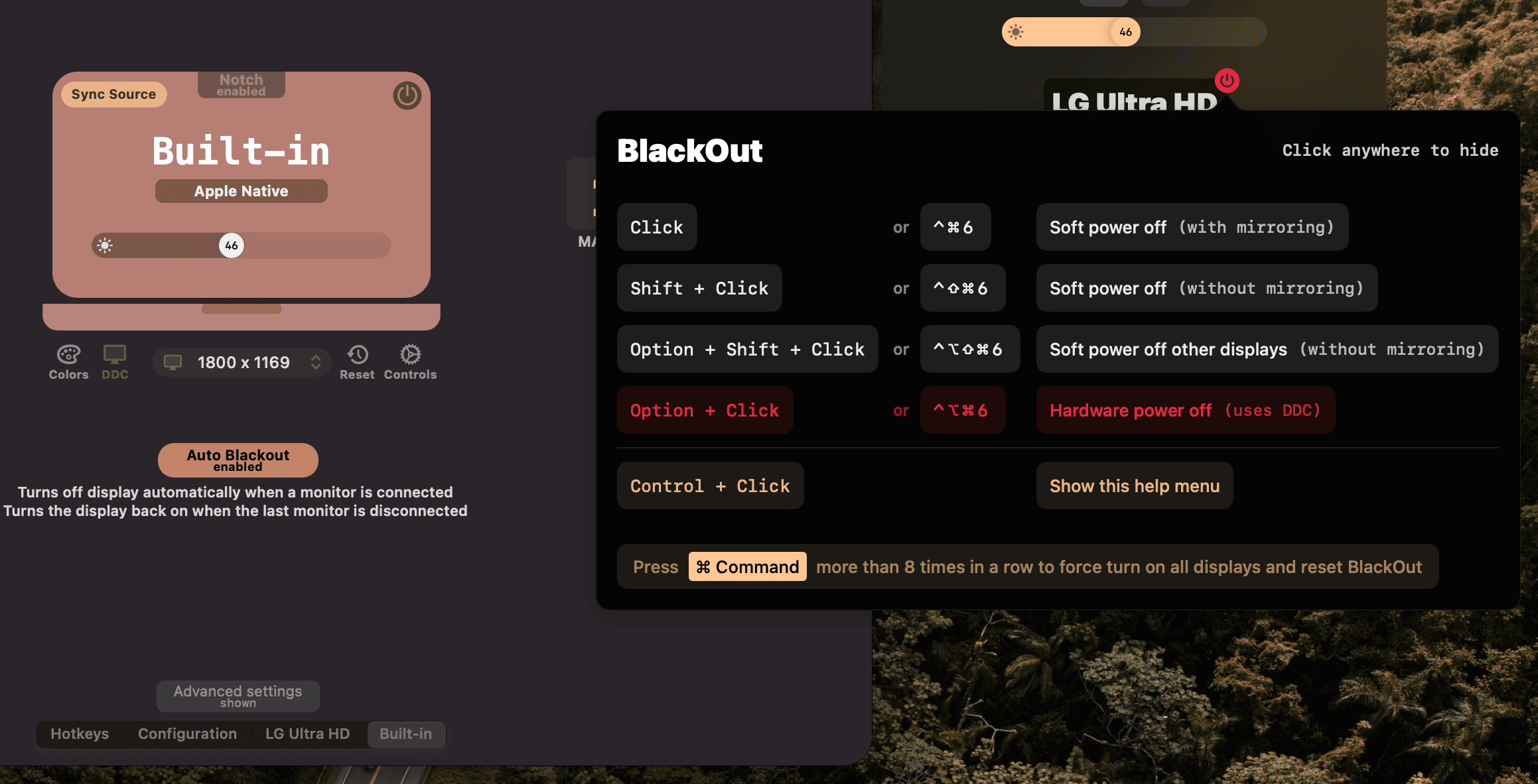

BlackOut

Because a lot of users of my 🌕 Lunar app told me about their grievances with not being able to turn off individual displays in software, I went down the rabbit hole of display mirroring and automated all of the above.

Now someone can turn off and on any display at will using keyboard shortcuts, and can even automate the above MacBook + monitor workflow to trigger when an external monitor gets connected and disconnected.

But it’s still nagging me that somehow macOS can actually disable the internal screen completely, but we’re stuck with this zero-brightness-mirroring abomination.

# Clamshell Mode

When closing the MacBook lid while a monitor is still connected, the internal screen disappears from the screen list and the external monitors remain available.

This function is called clamshell mode in the laptop world. Congratulations, your $3000 all-in-one computer is now just an SoC with some USB-C ports. Ok, you also get the speakers and the inefficient cooling system.

In the pre-chunky-MacBook-Pro-with-notch era, the lid was detected as being closed using magnets in the lid, and some hall effect sensors. So you were able to trick macOS into thinking the lid was closed by simply placing two powerful magnets at its sides.

With the new 2021 design, the MacBook has a hinge sensor, that can detect not only if the lid is closed, but also the angle of its closing. Magnets can’t trick’em anymore.

But all these sensors will probably just trigger some event in software, where a handler will decide if the display should be disabled or not, and call some disableScreenInClamshellMode function.

So where is that function, and can we call it ourselves?

# The software side

Since Apple Silicon, most userspace code lives in a single file called a DYLD Shared Cache. Since Ventura, that is located in a Cryptex (a read-only volume) at the following path:

/System/Cryptexes/OS/System/Library/dyld/dyld_shared_cache_arm64e

Since that file is mostly an optimised concatenation of macOS Frameworks, we can extract the binaries using keith/dyld-shared-cache-extractor:

|

|

Let’s extract the exported and unexported symbols in text format to be able to search them easily using something like ripgrep.

I’m using /usr/bin/nm with fd’s -x option to take advantage of parallelisation. I like its syntax more than parallel’s since it has integrated interpolation for the basename/dirname of the argument (note the {/})

|

|

Searching for clamshell gives us interesting results. The most notable is this one inside SkyLight:

|

|

SkyLight.framework is what handles window and display management in macOS and it usually exports enough symbols that we can use from Swift so I’m inclined to follow this path.

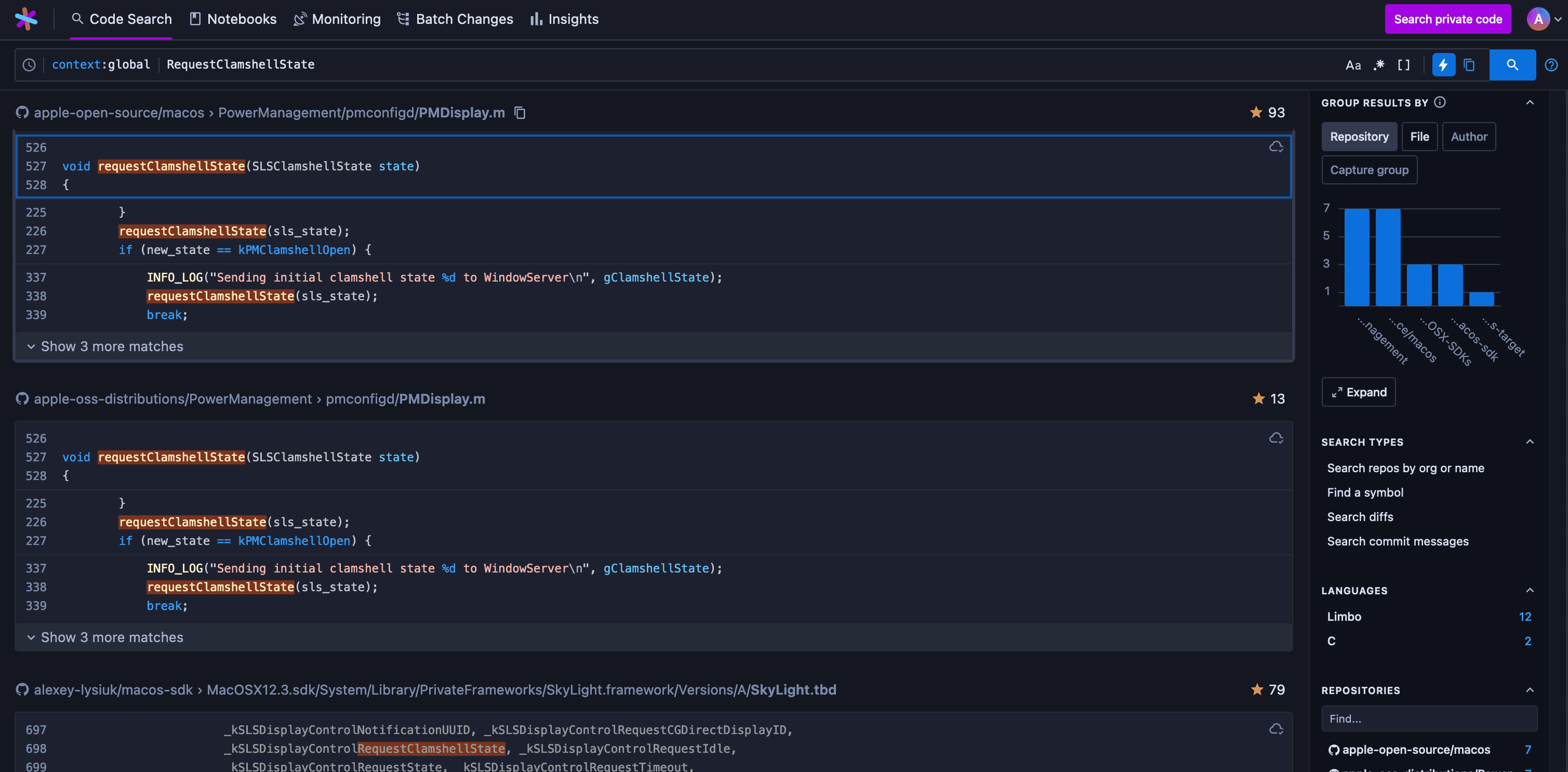

Let’s see if the internet has anything for us. I usually search for code on SourceGraph as it has indexed some large macOS repos with dyld dumps. Looking for RequestClamshellState gives us something far more interesting though:

Looks like Apple open sourced the power management code, nice! It even has recent ARM64 code in there, are we that lucky?

Here’s an excerpt of something relevant to our cause:

|

|

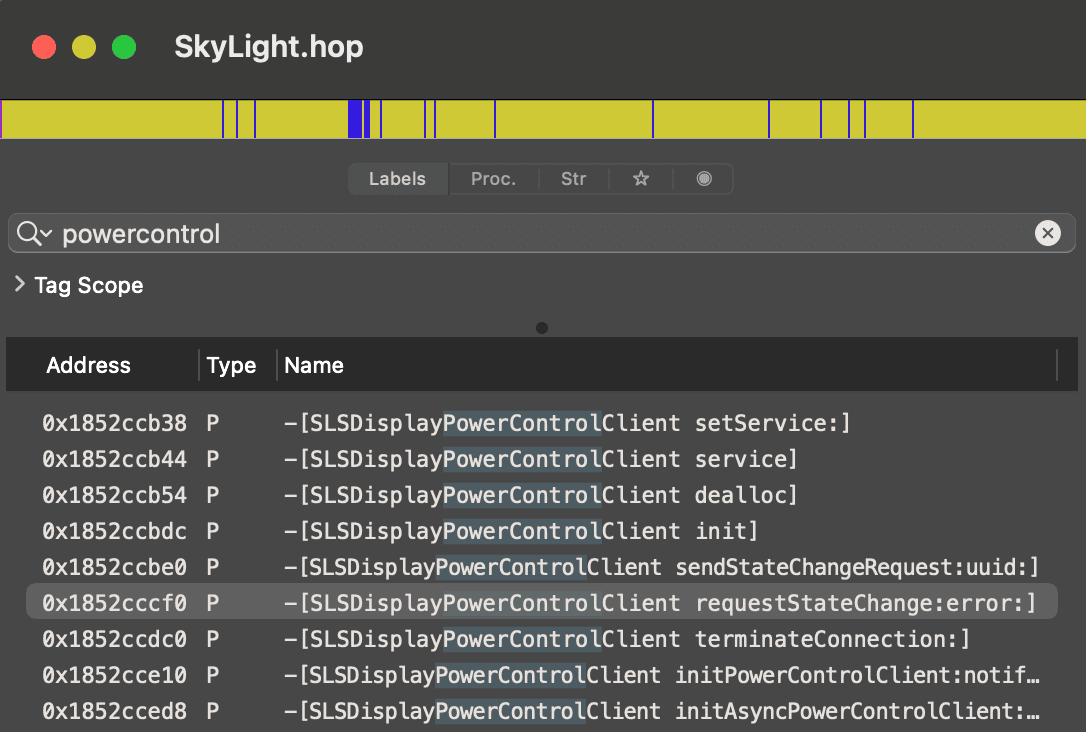

So it’s instantiating an SLSDisplayPowerControlClient then calling its requestStateChange method. SLS is a prefix related to SkyLight (probably standing for SkyLightServer), let’s see if we have that code in our version of the framework.

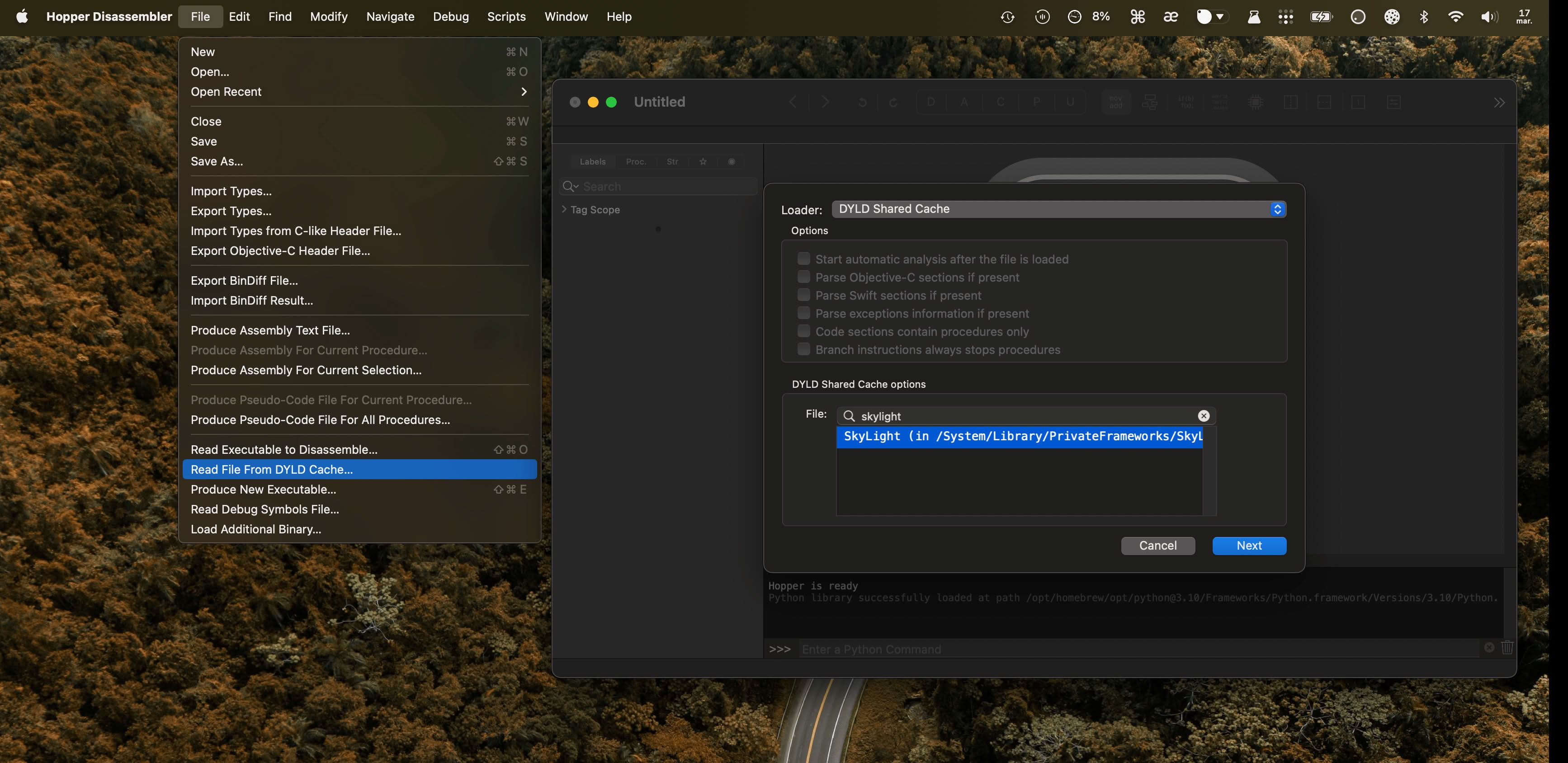

I prefer to do that using Hopper and its Read File From DYLD Cache feature which can extract a framework from the currently in-use cache:

Ok the class and methods are there, let’s look for what uses them. Since it’s most likely a daemon handling power management, I’ll look for it in /System/Library.

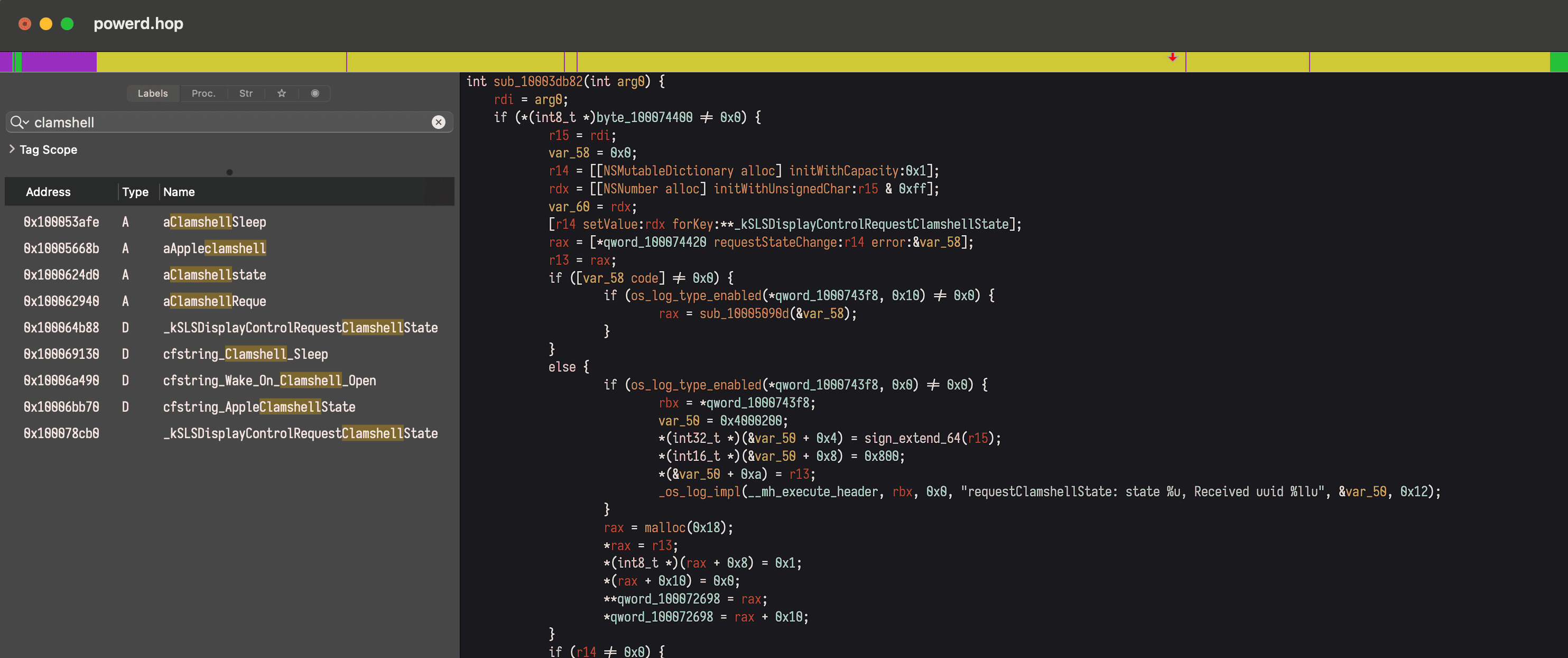

And looks like powerd is what we’re looking for, containing exactly the code that we saw on SourceGraph.

|

|

# Writing the code

To link and use SLSDisplayPowerControlClient we need some headers, as Swift doesn’t have the method signatures available.

Looking for SLSDisplayPowerControlClient on SourceGraph gives us more than we need.

Let’s create a bridging header so that Swift can link to Objective-C symbols, and a Swift file to where we’ll try to replicate what powerd does.

|

|

# Bridging-Header.h

|

|

# Clamshell.swift

|

|

# Compiling…

To compile the binary using swiftc we have to point it to the location of SkyLight.framework which is located at /System/Library/PrivateFrameworks.

We then tell it to link the framework using -framework SkyLight and import our bridging header. Then we run the resulting binary.

I prefer to run this using entr to watch the files for changes. With the code editor on the left and the terminal on the right, I can iterate and try things faster by just editing and saving the file, then watch the output on the right.

|

|

Well.. it’s not working. The error is not helpful at all, there’s nothing on the internet related to it.

|

|

# Looking for errors

Maybe the system log has something for us. One can check that using Console.app but I prefer looking at it in the Terminal through the /usr/bin/log utility.

|

|

Something from AMFI about the binary signature. CMS stands for Cryptographic Message Syntax which is what codesign adds to a binary when it signs it with a certificate.

|

|

I have GateKeeper disabled and running the binary from a terminal that’s added to the special Developer Tools section of Security & Privacy, so this shouldn’t cause any problems.

I checked just to be sure, and signing it with my $100/year Apple Developer certificate gets rid of the CMS blob error but doesn’t change anything in the result.

Phew, let's take a break

I just arrived after a long train ride at the house I'm rebuilding with my wife, and wanted to share this nice view with you 😌

It's January, but the sun is warming our faces and the hazelnut trees are already producing their yellow catkins.

Ten years ago, the children of the house's previous owners were walking in knee deep snow and coasting downhill on their wooden sleds, hurting a few young fir trees on the way down. 🌲

Seasons are changing.

# Digging deeper

Some system capabilities can only be accessed if the binary has been signed by Apple and has specific entitlements. Checking for powerd’s entitlements gives us something worrying.

The binary seems to use com.apple.private.* entitlements. This usually means that some APIs will fail if the required entitlements are not present.

|

|

We can try to add the entitlements ourselves. We just need to create a plist file and use it in codesign:

# Entitlements.plist

|

|

Sign the binary with entitlements and run it:

|

|

Looks like we’re getting killed instantly. The log stream shows AMFI is doing that because we’re not Apple and we’re not supposed to use that entitlement.

|

|

# AMFI

What’s this AMFI exactly and why is it telling us what we can and cannot do on our own device?

The acronym stands for Apple Mobile File Integrity and it’s the process enforcing code signature at the system level.

By default, the OS locks these private APIs because if we would be able to use them, a malware or a bad actor would be able to do it as well. With it locked by default, malware authors are deterred from trying to use these APIs on targets of lower importance as this would usually need a 0-day exploit.

In the end it’s just another layer of security, and if in the rare case someone needs to bypass it, Apple provides a way to do it. The process involves disabling System Integrity Protection and adding amfi_get_out_of_my_way=1 as a boot arg.

|

|

I don’t recommend doing this as it puts you at great risk, since the system volume is no longer read only, and code signatures are no longer enforced.

I only keep this state for research that I do in short periods of time, then turn SIP back on for normal day to day usage.

In case you need to revert the above changes:

|

|

# No more AMFI?

Unfortunately even after disabling AMFI, we’re still encountering the CoreGraphicsError 1004. It’s true, AMFI is not complaining about the entitlements anymore, they’re accepted and the binary is not SIGKILLed.

But we still can’t get into clamshell mode using just software.

Frida

If you haven’t heard of it, Frida is this awesome tool that lets you inject code into already running processes, hook functions by name (or even by address), observe how and when they’re called, check their arguments and even make your own calls.

Let me share with you another macOS boot arg that I like:

|

|

This one enables code injection. Now we can use Frida to hook the SkyLight power control methods to see how they are called as we close and open the lid:

|

|

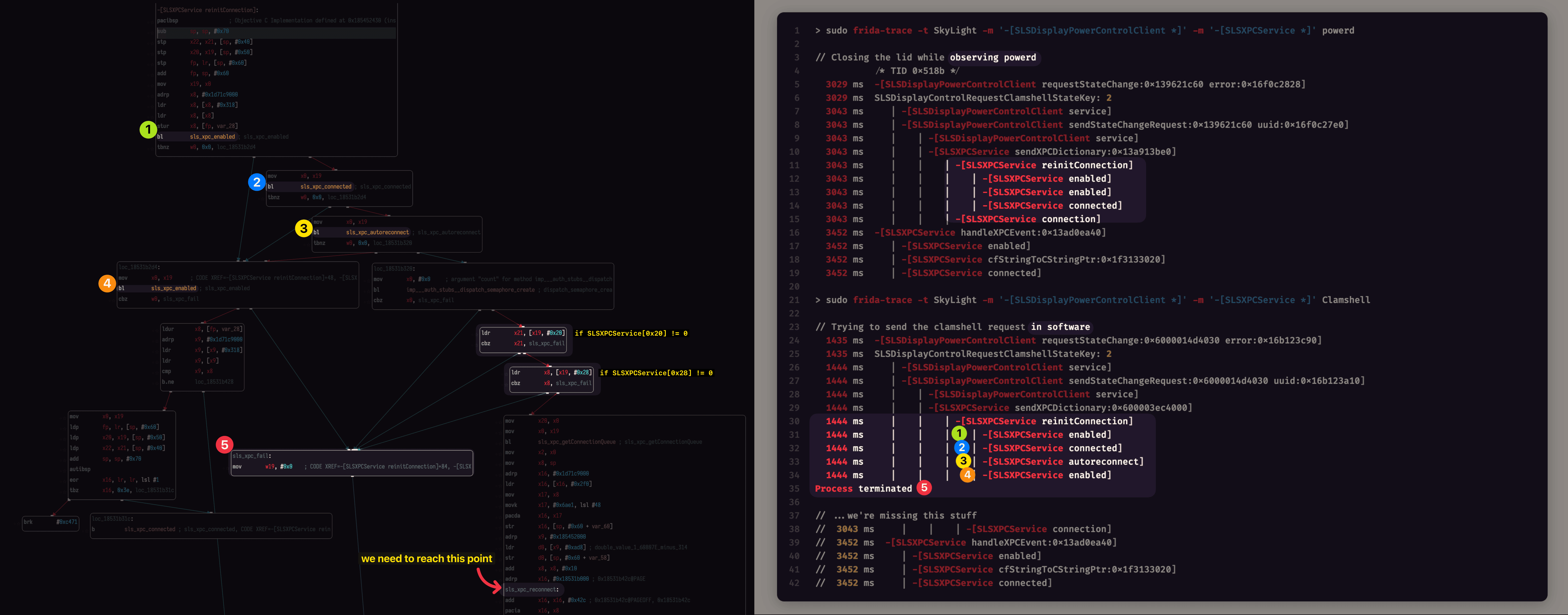

We got our confirmation at least. powerd is indeed calling SLSDisplayPowerControlClient.requestStateChange(2) when closing the lid.

Let’s check what happens when we try to call that method in Clamshell.swift.

We first add the line readLine(strippingNewline: true) at the top of the Clamshell.swift file to make the binary wait for us to press Enter. This is so that we have a running process that we can attach to with Frida.

|

|

Everything looks the same, seems that we’re not looking deep enough.

The request method seems to access the service property which is an SLSXPCService. XPC Services are what macOS uses for low-level interprocess communication.

A process can expose an XPC Service using a label (e.g. com.myapp.RemoteControlService) and listen to requests coming through, other processes can connect to it using the same label and send requests.

The system handles the routing part. And the authentication part.

Looks like an XPC Service can also be restricted to specific code signing requirements, is it possible that this is what we’re running into here?

Let’s trace SLSXPCService methods as well using Frida:

|

|

Great! or not?

I’m not sure if I should be happy that we found that our clamshell request doesn’t work because we don’t have an XPC connection, or if I should be worried that this means we won’t be able to make this work with SIP enabled.

I guess it’s time to go deeper to find out.

# XPC Services

Now that we have access to Frida, we can use the handy xpcspy tool to sniff the XPC communication of powerd.

I’m thinking maybe we can find the endpoint name of the XPC listener and just connect to it and send a raw message directly, instead of relying on SkyLight to do that.

|

|

So we have name = (anonymous), listener = false, pid = 30630.

An anonymous listener, can it get even worse? The PID coincides with WindowServer --daemon so it’s definitely the message we’re also trying to send. But with an anonymous listener, we’re stuck to relying on SkyLight’s exported code to reach it.

I guess we need to go back to do some old-school assembly reading.

# Filling empty spaces

After renaming some sub-procedures in Hopper, looking at the graph reveals the different code paths that powerd and Clamshell are taking through SLSXPCService.reinitConnection.

# powerd

- sees that the service’s

enabledandconnectedproperties aretrue - so it gets out of

reinitConnection - and straight into sending the XPC dictionary through the available

connection.

# Clamshell

- sees that

enabled,connectedandautoreconnectarefalse- so it fails with a

CGError

- so it fails with a

- if those properties were

trueit would go on the right-side code path which- checks if properties at

0x20and0x28are non-zero - then proceeds to reconnect.

- checks if properties at

Adding some Memory.readPointer calls inside __handlers__/SLSXPCService/reinitConnection.js shows us what SkyLight is expecting to see at 0x20 and 0x28:

Two NSMallocBlocks right after the OS_xpc_connection and the OS_dispatch_queue_serial properties.

|

|

Judging by the contents of SLSXPCService.h, those are the closures for errorBlock and notificationBlock:

|

|

I’m inching closer to the good code path but I seem to never get there.

So here’s what I did so far in Clamshell.swift before calling requestClamshellState:

|

|

After calling requestClamshellState, the code crashes with SIGSEGV inside createNoSenderRecvPairWithQueue:errorHandler:eventHandler: because it branches to the 0x0 address.

|

|

# Giving up (for now)

Unfortunately I’m a bit lost here. I’ll take a break and hope that the solution comes in a dream or on a long walk like in those mythical stories.

The article is already longer than I’d be inclined to read so if anyone reaches this point, congrats, you have the patience of a monk.

If there are better ways to approach a problem like this one, I’d be glad to hear about it through the contact form.

I’m not always happy to learn that I’ve wasted 4 days on a problem that could have been solved in a few hours with the right tools, but at least I’ll learn how not to bore people with writings on rudimentary tasks next time.

- Posted on:

- January 17, 2023

- Length:

- 19 minute read, 4002 words

- Categories:

- macOS reverse engineering