The journey to controlling external monitors on M1 Macs

How the transition to Apple Silicon made all monitor-controlling apps useless overnight, and how Lunar got past that

July 16, 2021

One lazy evening in November 2020, I watched how Tim Cook announced a fanless MacBook Air with a CPU faster than the latest 16 inch MacBook, while my work-provided 15 inch 2019 MacBook Pro was slowly frying my lap and annoying my wife with its constant fan noise.

I had to get my hands on that machine. I also had the excuse that users of my app couldn’t control their monitor brightness anymore, so I could justify the expense easily in my head.

So I got it! With long delays and convoluted delivery schemes because living in a country like Romania means incredibly high prices on everything Apple.

This already starts to sound like those happy stories about seeing how awesome M1 is, but it’s far from that.

This is a story about how getting an M1 made me quit my job, bang my head against numerous walls to figure out monitor support for it and turn an open source app into something that I can really live off without needing a “real job”.

# Adjusting monitor brightness on Intel Macs

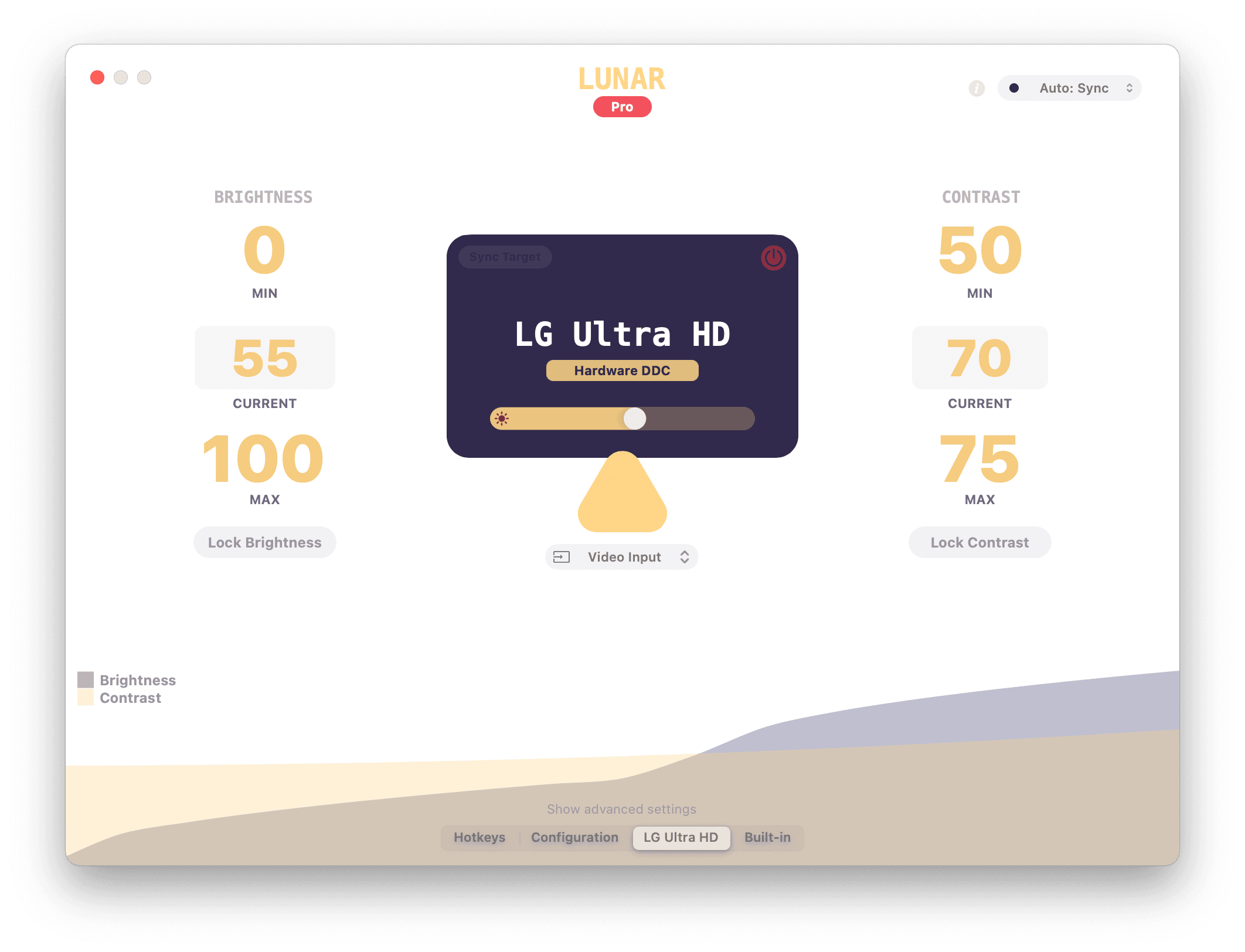

I develop an app called Lunar that can adjust the real brightness, contrast and volume of monitors by sending DDC commands through the Mac GPU.

# Useful links

On Intel Macs this worked really well because macOS had some private APIs to find the framebuffer of a monitor, send data to it through I²C, and best of all, someone has already done the hard part in figuring this out in this ddcctl utility.

M1 Macs came with a different kernel, very similar to the iOS one. The previous APIs weren’t working anymore on the M1 GPU, the IOFramebuffer was now an IOMobileFramebuffer and the IOI2C* functions weren’t doing anything.

All of a sudden, I was getting countless emails, Twitter DMs and GitHub issues about how Lunar doesn’t work anymore on macOS Big Sur (most M1 users were thinking the OS upgrade was causing this, disregarding the fact that they’re now using hardware and firmware that was never before seen on the Mac)

This was also a reality check for me. Without analytics, I had no idea that Lunar had so many active users!

# Constructing the DDC request

|

|

# Sending the data through I²C

|

|

# Hands-on with the M1

It was the last day of November. Winter was already coming. Days were cold and less than 10km away from my place you could take a walk through snowy forests.

snowy forests in Răcădău (Braşov, Romania)

But I was fortunate, as I had my trusty 2019 MacBook Pro to keep my hands warm while I was cranking code that will be obsolete in less than 6 months on my day job.

Just as the day turned into evening, the delivery guy called me about a laptop: the custom configured M1 MacBook Pro that costed as much as 7 junior developer monthly salaries has arrived!

After charging the laptop to 100%, I started the installation of my enormous Brewfile and left it on battery as an experiment. Meanwhile I kept working on the 2019 MacBook because my day job was also a night job when deadlines got tight.

Before I went to sleep, I wanted to test Lunar just to get an idea of what happens on M1. I launched it through Rosetta and the app window showed up as expected, every UI interaction worked normally but DDC was unresponsive. The monitor wasn’t being controlled in any way. I just hoped this was an easy fix and headed to bed.

# Workarounds

So it turns out the I/O structure is very different on M1 (more similar to iPhones and iPads than to previous Macs). There’s no IOFramebuffer that we can call IOFBCopyI2CInterfaceForBus on. There’s now an IOMobileFramebuffer in its place that has no equivalent function for getting an I²C bus from it.

After days of sifting through the I/O Registry trying to find a way to send I²C data to the monitor, I gave up and tried to find a workaround.

I realized I couldn’t work without Lunar being functional. I went back to doing the ritual I had to do in the first days I got my monitor and had no idea about DDC:

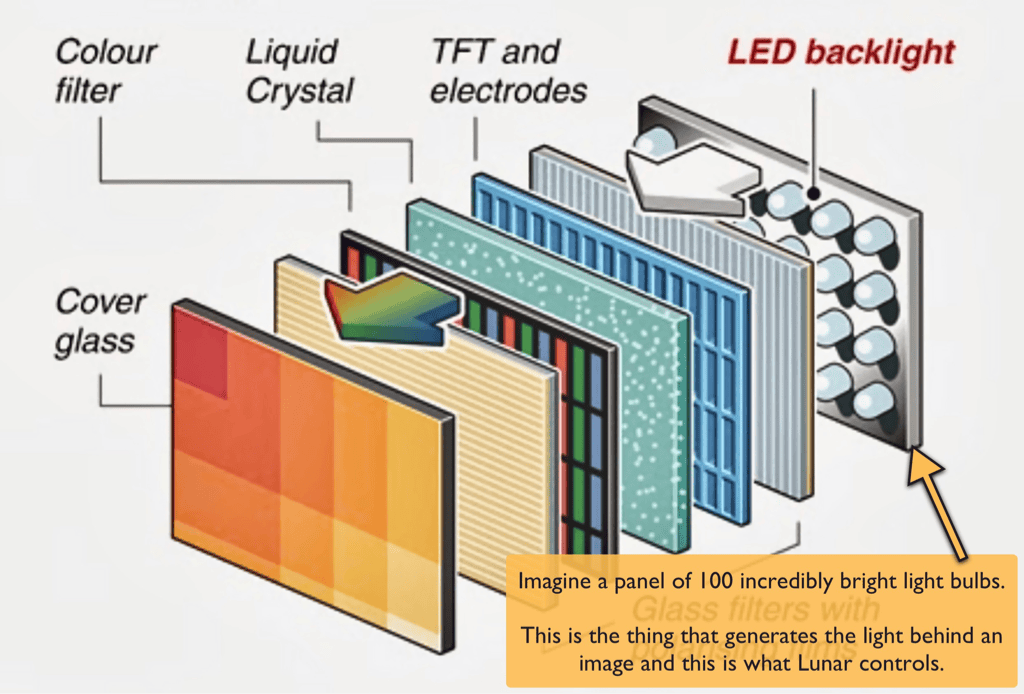

- Every evening I notice eye fatigue and a mild headache because the monitor is blinding me with its incredibly bright LED backlight (might also be that I’m reaching the 10th hour of working but who counts)

- Go through nested menus with an annoying joystick to lower the brightness and contrast

- Repeat about 3-5 times until I get too tired to do any more work

- Wake up in the morning

- Make coffee

- Get anxious about how much work there is to be done to meet the deadline

- Try to get back to work but now I can’t see a thing on the monitor because it has the brightness and contrast set to almost 0 from the night before

- Go through the same annoying menus to increase the brightness and contrast

- Repeat throughout the day

# Gamma Tables

One specific comment was becoming prevalent among Lunar users:

QuickShade works for me on M1. Why can’t Lunar work?

QuickShade uses a black overlay with adjustable opacity to lower the image brightness. It can work on any Mac because it doesn’t depend on some private APIs to change the brightness of the monitor.

it also makes colors look more washed out in low brightness

Actually, unlike Lunar, QuickShade doesn’t change the monitor brightness at all.

QuickShade simulates a lower brightness by darkening the image using a fullscreen click-through black window that changes its opacity based on the brightness slider. The LED backlight of the monitor and the brightness value in its OSD stay the same.

This is by no means a bad critique of QuickShade. It is a simple utility that does its job very well. Some people don’t even notice the difference between an overlay and real brightness adjustments that much so QuickShade might be a better choice for them.

LED monitor basic structure

I thought, that isn’t what Lunar set out to do, simulating brightness that is. But at the same time, a lot of users depend on this app and if it could at least do that, people will be just a bit happier.

So I started researching how the brightness of an image is perceived by the human eye, and read way too much content about the Gamma factor.

Here’s a very good article about the subject: What every coder should know about Gamma

I noticed that macOS has a very simple way to control the Gamma parameters so I said why not?. Let’s try to implement brightness and contrast approximation using Gamma table:

|

|

Of course this needed weeks of refactoring because the app was not designed to support multiple ways of setting brightness (as it usually happens in every single-person hacked up project).

And there were so many unexpected issues, like, why does it take more than 5 seconds to apply the gamma values?? ლ(╹◡╹ლ)

It seems that the gamma changes become visible only on the next redraw of the screen. And since I was using the builtin display of the MacBook to write the code and the monitor was just for observing brightness changes, it only updated when I became too impatient and moved my cursor to the monitor in anger.

Now how do I force a screen redraw to make the gamma change apply instantly? (and maybe even transition smoothly between brightness values)

Just draw something on the screen ¯\_(ツ)_/¯

I chose to draw a (mostly hidden) blinking yellow dot when a gamma transition happens, to force screen redraw.

# The Raspberry Pi idea

Now I was prepared to release a new version of Lunar with the Gamma approximation thing as a fallback for M1. But as it happens, one specific user sends me an email of how he managed to change the brightness of his monitor from a Raspberry Pi connected to the HDMI input, while the active input was still set to the MacBook’s USB-C.

I have already explored this idea as I have numerous Pis laying around, but I couldn’t get it working at all. I started writing a condescending reply of how I already tried this and how it will never work and he probably just has a monitor that happens to support this and won’t apply for other users.

But then… I realized what I was doing and started pressing backspace backspace backspace… and all the while I was remembering how the best features of Lunar were in fact ideas sent by users and I should stop thinking that I know better.

Instead, I started asking questions:

- what OS was the Pi running?

- was there a specific boot configuration he was using?

- what software was he using to send DDC requests?

I probably asked the right questions because the reply was exactly what I needed to get this working right away.

After 30 minutes of downloading the latest Raspberry Pi OS with full desktop environment, flashing it, updating to a beta firmware version, and setting the right values in /boot/config.txt, the Pi was able to send DDC requests using ddcutil while the monitor was rendering the MacBook desktop.

I couldn’t let this slip away, so I started implementing a network based DDC control for the next version of Lunar:

- a server would run on the Pi and listen for

/:monitor/:control/:value - the server will advertise itself on the network using mDNS so that Lunar won’t have to scan the whole LAN every x seconds

- Lunar will send the brightness, contrast, volume and input values to the server using simple HTTP requests

- the server will call ddcutil with the parameters from the request

I established from the start that the local network latency and HTTP overhead was negligible compared to the DDC delay so I didn’t have to look into more complex solutions like USB serial, websockets or MQTT.

# The dreaded day job

Even though side project is such a praised thing in the software development world, I can’t recommend doing such a thing.

It was very hard doing all of the above in the little time I had after working 9+ hours fullstack at an US company (that was also going through 2 different transitions: bought by a conglomerate, merging with another startup).

I owe a lot to my manager there, I wouldn’t have had the strength to do what followed without his encouraging advice and always present genuine smile.

One day, he told me that he finally started working on a bugfix for a long-standing problem in our gRPC gateway. He confessed that it was the first time in two months he found the time to write some code (the thing he actually enjoyed), between all the meetings and video calls. 10 minutes later, another non-US based team needed his help and his coding time got filled with scheduled meetings yet again. That is the life of a technical manager.

Now that Lunar was working on M1 and the Buy me a Coffee donations showed that people find value in this app, I thought it was time to stop doing what I don’t like (working for companies on products that I never use) and start doing what I always seemed to like (creating software which I also enjoy using, and share it with others).

So on April 1st I finished my contract at the US company, and started implementing a licensing system in Lunar.

Sounds simple right? Well it’s far from that. Preparing a product for the purpose of selling it, took me two whole months. And more energy than I put in 4 months of experimenting with Gamma and DDC on M1 (yeah, that was the fun part). This part of the journey is the hardest, and not fun at all.

My take from this is: if you’re at the start of selling your work, choose a payment or licensing solution that requires the least amount of work, no matter how expensive it may seem at first.

I went with Paddle for Lunar because of the following reasons:

- they have a macOS SDK, which meant

- no need to implement checkout views, license activation dialogs, guarding access to the app etc.

- the users can buy the license directly from the app, no need to redirect them to a website

- anti-cracking techniques are already better implemented than what I could have done in a few months time

- they act as a reseller which means they handle all the taxes

- I just get a pay-check on the 1st of each month

Even with that, I made the mistake to choose a licensing system that wasn’t natively supported by Paddle and that made me dig into a 2-month rabbit hole of licensing servers.

I wanted the system that Sketch has: a one-time payment for an unlimited license, that also includes 1 year of free updates.

# I²C on M1

After a successful launch in June, most users were happy with the Gamma solution, and some even tried the Raspberry Pi method: Lunar.app - a way for M1 Macs to control 3rd Party Monitor’s Brightness and Contrast - Hardware - MPU Talk

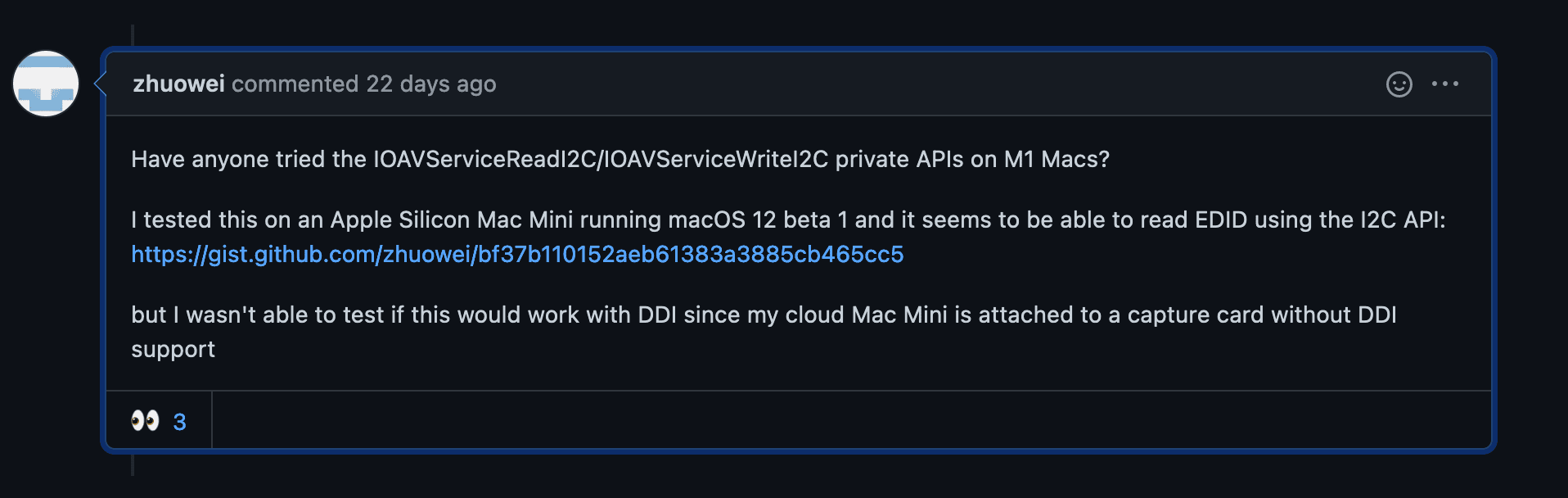

Although one user was still persistent in looking for I²C support. Twice he tried to bring to my attention a way to use I²C on M1 and the second time he finally succeeded.

- GIthub comment with I²C functions on M1

- Twitter reply from 3 months before, that I totally missed because I don’t use Twitter

His GitHub comment on the M1 issue for Lunar sparked a new hope among users and some of the more technical users started experimenting with the

IOAVServiceReadI2C and IOAVServiceWriteI2C functions.

Because of my shallow understanding of the DDC specification at the time, I couldn’t get a working proof of concept in the first few tries.

I didn’t know exactly what chipAddress and dataAddress were for

|

|

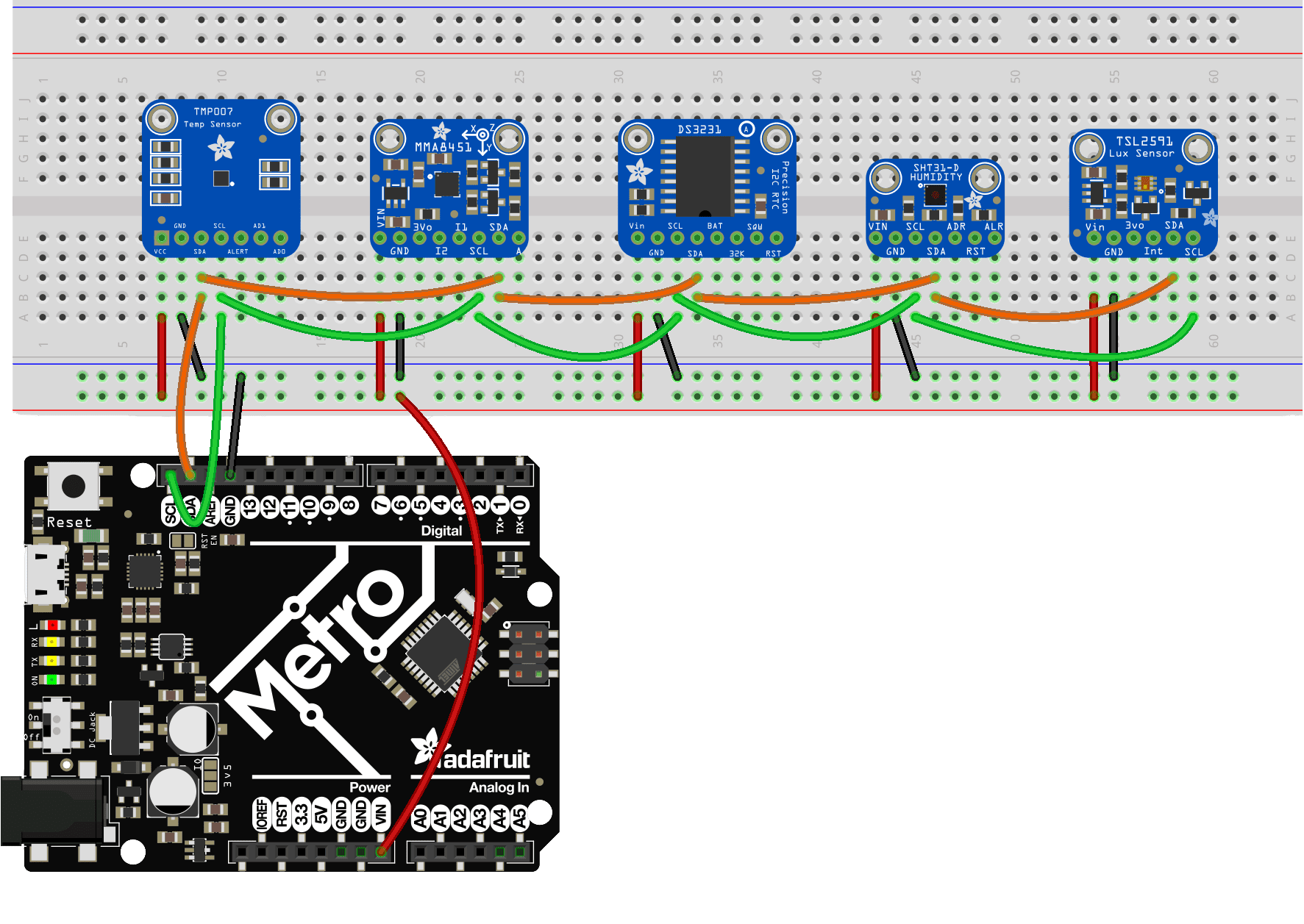

I knew from my experiments with ESP32 and Arduino boards that I²C is in fact a serial bus, which means you can communicate with more than one device from the same 2 pins of the main device by chaining the secondary devices.

That possibility brings the requirement of a chip address which the main device should send over the wire to reach a specific device from that chain.

chaining sensor boards through I²C

In the DDC standard, the secondary device is the monitor and has the chip address 0x37.

The EDID chip is located at the address 0x50 which is what we have in @zhuowei’s EDID reading example

|

|

But then what is the dataAddress?

No idea, but thankfully someone reverse engineered the communication protocol and found this to always be 0x51.

After some trial and error, user @tao-j discovered the above details and managed to finally change the brightness from his M1 MacBook.

# The Mac Mini problem

Unfortunately, this was just the beginning as the Mac Mini supports more than one monitor and it’s not clear what monitor we’re controlling when calling IOAVServiceCreate().

I found a way to get each monitor’s specific AVService by iterating the I/O Kit registry tree and looking for the AppleCLCD2 class. To know which AppleCLCD2 belonged to what monitor, I had to cross reference identification data returned by CoreDisplay_DisplayCreateInfoDictionary with the attributes of the registry node.

With that convoluted logic, I managed to get DDC working on Mac Mini as well, but only on the Thunderbolt 3 port. The HDMI port still doesn’t work for DDC, and no one knows why.

In the end, DDC on M1 was finally working in the same way it worked on Intel Macs!

# Sending I²C data on M1

|

|

Some quirks are still bothering the users of Lunar though:

- some monitors lose signal or flicker in and out of connecting when the M1 GPU sends any I²C data

- the HDMI port of the Mac Mini doesn’t send any kind of data over I²C

- reading the currently visible input through DDC never works on M1

- reading brightness, contrast or volume from the monitor fails about 30% of the time

For the moment these seem to be hardware problems and I’ll just have to keep responding to the early morning support emails no matter how obvious I make it that these are unsolvable.

# Technical stuff

I left these at the end because the details may bore most people but they might still be useful for a very small number of readers.

# How is an app able to change the hardware brightness of a monitor?

All monitors have a powerful microprocessor inside that has the purpose of receiving video data over multiple types of connections, and creating images from that data through the incredibly tiny crystals of the panel.

That same microprocessor dims or brightens a panel of LEDs behind that panel of crystals based on the Brightness value that you can change in the monitor settings using its physical buttons.

Because the devices that connect to the monitor need to know stuff about its capabilities (e.g. resolution, color profile etc), there needs to be a language known by both the computer and the monitor so that they can communicate.

That language is called a communication protocol. The protocol implemented inside the processors of most monitors is called Display Data Channel or DDC for short.

To allow for different monitor properties to be read or changed from the host device, VESA created the Monitor Control Command Set (or MCCS for short) which works over DDC.

MCCS is what allows Lunar and other apps to change the monitor brightness, contrast, volume, input etc.

# Then what the heck is I²C?

I²C is a Wire protocol, which basically specifies how to translate electrical pulses sent over two wires into bits of information.

DDC specifies which sequences of bits are valid, while I²C specifies how a device like the monitor microprocessor can get those bits through wires inside the HDMI, DisplayPort, USB-C etc. cables.

# Why does macOS block me from changing volume on the monitor, while Windows allows that?

macOS doesn’t block volume, it simply doesn’t implement any way for you to change the volume of a monitor.

Windows actually only changes the software volume, so if your monitor real volume is at 50%, windows can only lower that in software so you’ll hear anything between 0% and 50%. If you check the monitor OSD, you’ll see that the volume value of the monitor always stays at 50%.

Now macOS could probably do that as well, so that at least we’d have a way to lower the volume. But it doesn’t.

So if you want to change the real volume of the monitor on Mac, Lunar can do that.

- Posted on:

- July 16, 2021

- Length:

- 17 minute read, 3452 words

- Categories:

- macOS reverse engineering